by Kevin Riehle

Who was the first Soviet intelligence penetration of the CIA? Kim Philby was the SIS liaison to the U.S. Intelligence Community during his tour in Washington from 1949 to 1951. However, although he had better access to the U.S. intelligence than most foreigners, he never had employee access. Karl Koecher, whom the CIA hired in the early 1970s, worked for the Czechoslovak StB, not the KGB. CIA officers Edward Lee Howard and Aldrich Ames did not initiate contact with the KGB until the 1980s.

Two less ambiguous candidates appear in the remote corners of Vasiliy Mitrokhin’s notes, which are available at the Churchill Archive Centre at Cambridge University.1 When Mitrokhin defected in 1992, he offered the SIS the stash of notes he had accumulated during his decades of service in the KGB First Chief Directorate archive.2

Among Mitrokhin’s notes is a draft unpublished manuscript titled The Accursed: In the Footsteps of Filth (Окаянщина: По Следам Скверны), which Mitrokhin finished compiling in 1988. Mitrokhin signed the manuscript with the strange pseudonym Nikhor Tim. Although not a typical Russian name, the pseudonym is “Mitrokhin” spelled backwards. The word “accursed” in the title refers to the Soviet regime, for which Mitrokhin had developed a deep hatred by the time he compiled the manuscript.

A chapter titled “Iran” gives an account of a Soviet husband-and-wife couple, Shota Vladimirovich Tkeshelashvili and Izabella Karapetovna Stepanyan. Shota had spent part of his teenage years in Iran while his father was working on the Trans-Iranian Railway, and the OGPU recruited him in Tabriz in 1931. Izabella served in the Soviet Army during World War II. The couple was enrolled as Soviet intelligence illegals likely in the late 1940s, given codenames SMIT and MERI, and crossed the Soviet border into Iran in 1952. Their mission was to emigrate to the United States, and they succeeded in doing so by contacting U.S. government representatives in Iran who accepted them as refugees. They arrived in New York in September 1954, and the CIA assigned them new names, Peter and Isabella Gorelli.3

The CIA hired them, and at an unspecified time after 1954, they moved to Greece, from where the CIA-sponsored Radio Kavkaz broadcast into Soviet Georgia. The CIA’s cryptonym for Radio Kavkaz was AEPARADE. Shota/Peter worked for the radio station, and Izabella was employed as a linguist translating signals intelligence intercepts. It is unclear what vetting process was done to clear them for CIA employment.

The CIA transferred them to the United States in 1960 when Radio Kavkaz closed, by which time they had worked in CIA-related jobs for about six years. Izabella was assigned to the CIA’s Soviet Division and Shota/Peter worked with CIA communications. They reported information to Moscow about the Agency and its employees, especially about other Soviet escapees who were working for the U.S. intelligence community. They also reported information about what U.S. intelligence knew about Soviet ballistic missile locations. Their information was highly valued in Moscow.

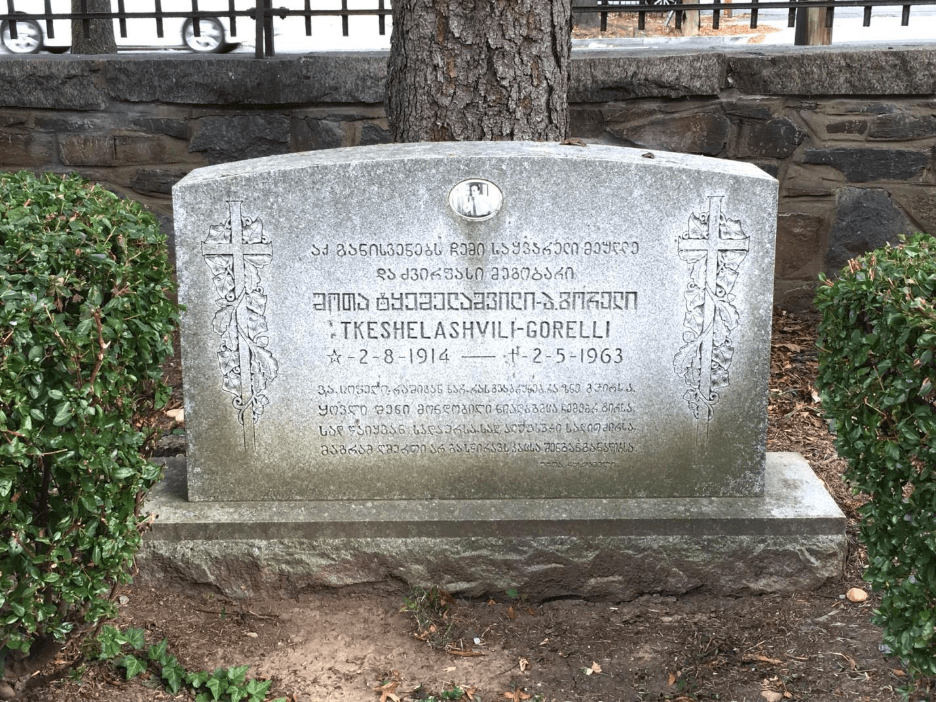

The KGB put them on ice temporarily after Anatoliy Golitsyn’s defection in December 1961; Moscow eventually concluded that Golitsyn knew nothing about them. However, in 1962, Shota/Peter was diagnosed with lung cancer. He chose to refuse treatment because he was afraid that if he were to undergo a surgical operation, he might blurt out something while under anesthesia that compromised his real identity. Consequently, he died in February 1963 and was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, DC. Mitrokhin noted that his headstone included a quote from Shota Rustaveli’s epic poem, “Knight in the Panther’s Skin”: “Fate is complex and it is never known what she is preparing for each of us. But even if fate betrays someone, God’s attention does not abandon him.”

Izabella moved to a new house and broke off communication with Moscow. The KGB located her, though, in 1965. Oleg Kalugin, who was nearing the end of his tour of duty in Washington, visited her, introduced himself as an employee of the Soviet embassy, and invited her to return to the Soviet Union.4 She had left her CIA position by that point and no longer had access to intelligence of value to the KGB. However, the KGB hoped to repatriate her, use her name in anti-CIA propaganda as it did with other re-defectors,5 and use her to approach another CIA employee and facilitate his KGB recruitment. She initially admitted to Kalugin that she was homesick and agreed to return, and the KGB Washington rezidentura arranged for her travel to Moscow via Athens and Beirut. She traveled as far as Athens but changed her mind and never appeared in Beirut, returning to the United States instead.

The KGB tried several more times to reestablish contact, including recruiting her nephew and sending him to the United States twice in the 1970s to persuade her return. She finally refused in 1979, explaining that she did not want to work against the CIA. Due to her age—she was 66 in 1979—the KGB decided to let it drop. She eventually moved to California and died there in 1998.

Kalugin gives a brief account of his interactions with Izabella but provides no names and glosses over some details; for example, he never mentions that she and her husband were Soviet illegals or that they had worked for the CIA. Nevertheless, although Mitrokhin’s and Kalugin’s versions of the story differ on minor details, they mesh in substance.

No mention of Tkeshelashvili and Stepanyan appears in Christopher Andrew’s books. Gordon Corera mentions Mitrokhin’s manuscript and the phrase “on the trail of filth” in his recent book about Mitrokhin6 but doesn’t mention Tkeshelashvili and Stepanyan. Mitrokhin himself published the first portion of the manuscript covering the KGB in Afghanistan through the Wilson Center Cold War International History Project in 2002. But large portions remain unpublished.

In any case, when the CIA hired them in about 1953, Tkeshelashvili and Stepanyan became the some of the first Soviet intelligence penetrations of the CIA.

- Mitrokhin Papers, MITN 1/2, pp. 58-59. ↩︎

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archives and the Secret History of the KGB (New York: Basic Books, 1999), pp. 13-14; Gordon Corera, The Spy in the Archive: How One Man Tried to Kill the KGB (London: William Collins, 2025). ↩︎

- WWII Alien Registration, 1940-1955, Ancestry.com. Tkesheleshvili registration number G033O01344; Stepanyan registration number G033O01319. ↩︎

- Oleg Kalugin, Spymaster: My Thirty-Two Years in Intelligence and Espionage Against the West (New York: Basic Books, 2009), pp. 109-110. ↩︎

- Others included Yuriy Pyatakov (aka Yuri Marin), who re-defected in 1973, and Oleg Tumanov, who re-defected in 1986. Both published KGB/SVR-inspired material criticising Radio Liberty after their redefection. ↩︎

- “On the trail of filth” is another translation for the phrase “in the footsteps of filth.” See Corera, The Spy in the Archive, pp. 143, 224. ↩︎

Leave a comment